Glossary of Terms

Osmosis

Osmosis is the flow of a (liquid) solvent through a semi-permeable (permeable only to the solvent) membrane when a solution is separated from a pure solvent by such a membrane. In osmosis the solvent moves from the solvent side to the solution side, while in reverse osmosis the solvent moves from the solution to the solvent side. Osmosis and reverse osmosis are fundamentally the same phenomenon, and governed by the same fundamental laws.

The French botanist Henri Dutrochet discovered the phenomenon of osmosis while studying plant cells. This phenomenon has been observed in biological systems, both animal and plant cells, and is also used in water purification and desalination, waste material treatment and various other industrial processes. Osmosis is a type of passive transport, that is, no energy is required for the molecules to move across the semi-permeable membrane. Osmosis is a reversible thermodynamic process, so that the direction of liquid solvent flow through the semi permeable membrane can be reversed at any moment by proper control of the external pressure on the solution. In contrast, consider the process of mixing a teaspoon full of sugar in a cup of tea. This is an irreversible thermodynamic process because it is not possible to reverse the process at any given moment and separate the sugar back into the spoon.

In biological systems, the most common solvent is water so the definition of osmosis can be modified to the passage of water from a region of high water concentration through a semi-permeable membrane to a region of low water concentration

Semi-permeable membranes

Semi-permeable membranes are thin layers of material, which allow some things to pass through them but prevent other things from passing through, for example, cell membranes. Cell membranes will allow small molecules like oxygen, water, carbon dioxide, ammonia, glucose, amino-acids, etc. to pass through, while not allowing larger molecules like sucrose, starch, protein, etc. to pass through.

Osmotic Pressure

Osmotic pressure is a colligative property in that for a dilute ideal solution it depends only on the mole fraction of the solute. It does not depend on the nature of the solute but only on the number of molecules in the solution. The transport of the solvent molecules across the membrane in osmosis stops when the hydrostatic pressure on the solution side is sufficiently high to prevent the flow of the solvent (by ensuring the chemical potential of the solvent on both sides of the membrane is equal). This extra pressure on the solution side necessary to counteract the forces of osmosis is called osmotic pressure. The osmotic pressure, , in the approximation of an ideal solution at low solute mole fraction is

where R = 0.0812 L atm / mol K

T = temperature in K

= molar volume of the solvent A

= mole fraction of solute B

Osmotic pressure measurements are used in the determination molecular mass of compounds like polymers and biologically important macromolecules.

The Effects of Osmosis

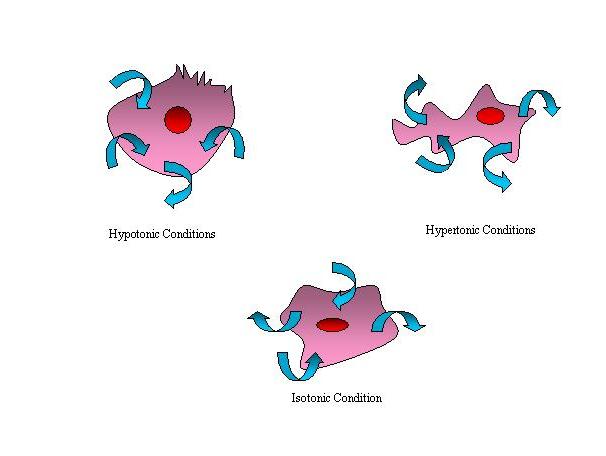

When an animal cell or a plant cell is placed in a medium, which is a water solution , the possible consequences are listed below.

1. If the water concentration of the cell's cytoplasm is lower then that of the medium (i.e. the medium is a hypotonic solution) surrounding the cell then osmosis will result in the cell gaining water. The water molecules are free to pass across the cell membrane in both directions, but more water molecules will enter the cell than will diffuse out with the result that water enters the cell, which will then swell up and could possibly burst.

2.If the water concentration inside the cell is the same as that in the surrounding medium (i.e. the medium is a isotonic solution) there will exist a dynamic equilibrium between the number of molecules of water entering and leaving the cell and so the cell will retain its original size. For example, the red blood cell in the blood plasma retains its shape because of the isotonic nature of the plasma.

3.If the water concentration inside the cell is higher then that of the medium (i.e. the medium is a hypertonic solution) the number of water molecules diffusing out will be more than that entering and the cell will shrink and shrivel due to osmosis.

Effects of osmosis in plant cells

Plant cells are enclosed by a rigid cell wall. When the plant cell is placed in a hypotonic solution , it takes up water by osmosis and starts to swell, but the cell wall prevents it from bursting. The plant cell is said to have become "turgid" i.e. swollen and hard. The pressure inside the cell rises until this internal pressure is equal to the pressure outside. This liquid or hydrostatic pressure called the turgor pressure prevents further net intake of water . Turgidity is very important to plants as it helps in the maintenance of rigidity and stability of plant tissue and as each cell exerts a turgor pressure on its neighbor adding up to plant tissue tension which allows the green parts of the plant to "stand up" into the sunlight.

When a plant cell is placed in a hypertonic solution , the water from inside the cell<92>s cytoplasm diffuses out and the plant cell is said to have become "flaccid". If the plant cell is then observed under the microscopic, it will be noticed that the cytoplasm has shrunk and pulled away from the cell wall .This phenomenon is called plasmolysis. The process is reversed as soon as the cells are transferred into a hypotonic solution (deplasmolysis).

When a plant cell is placed in an isotonic solution, a phenomenon called incipient plasmolysis is said to occur. "Incipient" means "about to be". Although the cell is not plasmolsysed, it is not turgid. When this happens the green parts of the plant droop and are unable to hold the leaves up into the sunlight.

Effects of osmosis in animal cells

Animal cells do not have cell walls. In hypotonic solutions, animal cells swell up and explode as they cannot become turgid because there is no cell wall to prevent the cell from bursting. When the cell is in danger of bursting, organelles called contractile vacuoles will pump water out of the cell to prevent this. In hypertonic solutions, water diffuses out of the cell due to osmosis and the cell shrinks. Thus, the animal cell has always to be surrounded by an isotonic solution. In the human body, the kidneys provide the necessary regulatory mechanism for the blood plasma and the concentration of water and salt removed from the blood by the kidneys is controlled by a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. The process of regulating the concentration of water and mineral salts in the blood is called osmoregulation Animals which live on dry land must conserve water and so must animals which live in the salty sea water, but animals which live in freshwater have the opposite problem; they must get rid of excess water as fast as it gets into their bodies by osmosis.

Dialysis

In a multi-component system, dialysis is a process by which only certain compounds including both the solvent molecules and small solute molecules are able to pass through the selectively permeable dialysis membrane but other larger components such as large colloidal molecules like proteins cannot pass through pores in the dialysis membranes . Dialysis can therefore be used for separation of proteins from small ions and molecules and hence is used for purification of proteins required for laboratory experiments. Examples of membranes through which dialysis occurs are animal bladders, parchment and cellophane (cellulose acetate).

The most important medical application of dialysis is in dialysis machines, where hemodialysis is used in the purification of blood from patients suffering from renal malfunction. Blood from the patient is circulated through a long cellophane dialysis tube suspended in an isotonic solution called the dialysate which is an electrolyte solution containing the normal constituents of blood plasma. The toxic end products of nitrogen metabolism such as urea from the blood pass through the dialysis membrane where they are removed while cells, proteins and other blood components are prevented by their size from passing through the membrane. Also, the dialysate concentration can be controlled so that salt , water and acid-base imbalances in electrolytes are corrected. Purified blood is then returned to the body.

Reverse Osmosis

Reverse osmosis is the process by which the liquid solvent moves across the semi-permeable membrane against its concentration gradient , i.e. , from high solvent concentration to low solvent concentration in the presence of externally applied pressure on the solution. This pressure must be larger than the osmotic pressure, so in general reverse osmosis can be energy intensive. The process of reverse osmosis requires this driving force to push the fluid through the membrane (which is again attempting to ensure that the chemical potential of the solvent on both sides becomes equal as required by equilibrium thermodynamics), and the most common force is pressure from a pump. The higher the pressure, the larger the net driving force. As the concentration of the fluid being rejected increases, the driving force required to continue concentrating the fluid increases (since the osmotic pressure increases with higher concentrations).

This process is also known as hyperfiltration as it is one of the best filtration methods known .The removal of particles as small as ions from a solution is made possible using this method. Reverse osmosis is most commonly used to purify water and desalination. It can also be used to purify fluids such as ethanol and glycol, which will pass through the reverse osmosis membrane, while rejecting other ions and contaminants from passing. Reverse osmosis is capable of rejecting bacteria, salts, sugars, proteins, particles, dyes, etc.

Formulation

The chemical potential of the solvent A at the constant temperature is a function of mole fraction of the solute B and external pressure P

Differentiating the above equation we get,

To prevent flow of the solvent

By definition of chemical potential we have,

where G is the Gibbs Free Energy

Thus,

Or,

For a dilute solution,

So,

Background Material

Books (Molecular Simulations and Reverse Osmosis)

M. P. Allen,and D. J. Tildesley, Computer Simulation of Liquids. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987.

J. M. Haile. Molecular dynamics: Elementary methods. New York: Wiley, 1992.

S. Sourirajan. Reverse Osmosis. New York: Academic Press, 1970.

Papers (Algorithm)

S. Murad, J. G. Powles. A computer simulation of the classic experiment on osmosis and osmotic pressure. J. Chem. Phys. 99: 7271, 1993.

S. Murad, P. Ravi, J. G. Powles. A computer simulation study of fluids in model slit, tubular and cubic micropores. J. Chem. Phys. 98: 9771, 1993.

S. Murad, J. G. Powles. Computer simulation of osmosis and reverse osmosis in solutions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 225:437, 1994.

S. Murad. Molecular dynamics of osmosis and reverse osmosis in solutions. Adsorption. 2: 95, 1996.

F. Paritosh, S. Murad. Molecular simulation of osmosis and reverse osmosis in aqueous electrolyte solutions. AIChE J. 42:2984, 1996.